The Japanese labour market is characterised by the lifetime employment system, seniority-based wages, and labour dualism. As this article will show, there is no evidence that the system of lifetime employment will change in the near future, although there is progress in the field of payment systems. Since Japan is facing the rapid ageing of its population and labour force changes must be made in Japan in order to maintain the strong competitive position in the global economy.

This article consists of four parts. The first part provides an insight into Japan’s population and labour force. The second and the third part describe the functioning of Japanese labour markets. Final remarks explaining why Japanese labour practices are under a threat is set out in the conclusion.

JAPAN’S POPULATION AND LABOUR FORCE

Japan's population was growing continuously for almost four decades, but in 2010 Japan’s population fell to the 2000 level, as showed in Figure 1. The population is expected to fall in the long run as the falling birth-rate and the aging population change the population composition (Statistics Bureau, 2011). Expectations are that by 2050 the Japan’s population will fall by 25 million people. Between 1970 and 2000, as Japan’s population grew, its labour force also increased. Thereafter the number of employed people started to fall and the unemployment rate increased and in 2010 it reached 5.1 per cent, still representing a very low unemployment rate relative to other developed countries . Throughout the observed period, almost half the population was employed. The reasons for the low unemployment rates are mainly attributable to the lifetime employment system, minimum wage laws, unemployment compensation and the demographic structure of the labour force (Flath, 2005).

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 1: Japan’s population and labour force

Source: The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training (2011)

Figure 2 shows the labour force participation rate by age group for both men and women in 1975 and 2009. The proportion of men who are members of the labour force are similar in each year, where the participation rate of men aged between 25 and 55 was over 95 per cent. The situation is different when considering the women’s participation rate. Even though the percentage of young women aged between 15 and 24, has not changed throughout the period, there is a significant change of participation rate of women aged 25 to 64. The percentage of women in the labour force increased, with respective percentage in the age group 24-29 increasing by 35 per cent, and other age groups experienced the change of 6 up to 14 per cent, but the percentage remained almost the same for women aged 65. In 1975 and 2009 the curves are shaped as a letter M and they indicate that women leave the labour force when they are starting a family and re-join the labour force after the burden of child-rearing is reduced (Statistic Bureau, 2011). The advance of technology and improved educational status of women have increased women’s labour productivity and therefore resulted in a greater participation rate (Flath, 2005). Women who follow this pattern are not included in lifetime employment system of large companies (Flath, 2005).

|

Figure 2: Labour force participation rate by sex and age group

Source: The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training

|

The largest proportion of Japanese women is in clerical and related jobs and in the protective and other services, where they account for over 50 per cent of the labour force in both 1980 and 2010. As shown in Figure 3, the proportion of female workers has consistently been very low in the transport and communication sector over the past 30 years. Women are also rarely employed as managers and officials, but they improved their status over the period. In general, Japanese women are not well-educated or career-minded and they earn substantially less than Japanese men (Flath, 2005) which can explain the small proportion of women as managers or similar occupations.

|

Figure 3: Percentage of female workers by occupation

Source: Statistical Handbook of Japan 2011 by Statistics Bureau |

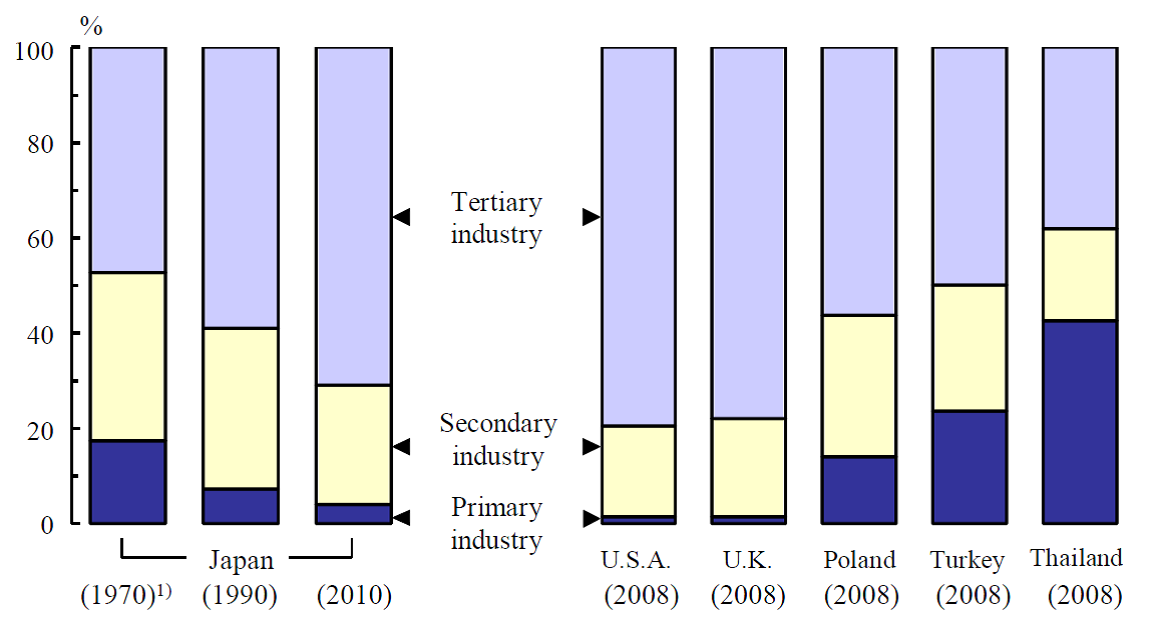

In the 40-year period the Japanese structure of employment has changed, hence the ratios of primary and secondary industries fell and tertiary industry rose and it is the main sector industry in Japan. More than 70 per cent of people are employed in the service industry .

|

Figure 4: Structure of employment by country

Source: Statistical Handbook of Japan 2011 by Statistics Bureau |

The Japanese employment structure nowadays is quite similar to the UK’s and the USA’s structure. This is not surprising since Japan, the UK and the USA are developed countries which are heavily weighted towards the service sector; in contrast, industries such as manufacturing and agriculture are the main industries for developing and emerging countries like Turkey, Thailand and of course China .

Since developing countries have a cheaper production (e.g. low cost labour, economies of scale) there is a big possibility that Japan will transfer its remained production and manufacturing plants to those countries in order to achieve global competitive advantages and at that time the ratio of primary and secondary industry will be even smaller. This can lead to the changes of the lifetime employment and payment systems in Japan.

PAYMENT SYSTEMS IN JAPAN

Japanese people during their lives rarely change their jobs and employers and receive a larger component of pay based strictly on the number of years of continual service, which represents the pattern of lifetime employment and seniority-based wages (Flath, 2005). The argument for seniority-based wage nenko system is that workers with more years of formal education and with longer experience in occupation have more skills and contribute more to the output and revenues of their employers; hence their services are in greater demand. In that case, the earnings of workers that possess skills will remain above those of workers who lack them. This system is used to control and motivate the employees of large companies. Furthermore, it discourages quits and increases the onerousness of early dismissal and has enabled large Japanese companies to economize on the costs of training employees in skills that are specific to their respective work-places, while preserving employee incentives to exert effort (Flath, 2005).

Rebick (2001) argues that the seniority-based wage system was common in the 1950s, but through the 1960s and 1970s almost all large companies adopted shokuno-shikaku seido or in other words, the ability-qualification wage payment system. In this system, workers are primarily paid according to the qualifications that they receive for developing skills but there are still some links to seniority in this payment system. Nowadays, many companies are moving away from the ability-qualification wage payment system by imposing the new payment system based on the ability shown through actual performance on the job. Due to a limited number of managerial positions, companies are more interested in the development of specialist skills through which workers can demonstrate their abilities.

A widespread practice in Japan is to reward workers by giving them bonuses twice a year and those bonuses are not given just to the senior executives, but also to any other employee, which is not the case in the USA (Flath, 2005). Moreover, bonuses account for a large proportion of overall annual earnings and they are not linked to individual performance but reflect the wider performance of the company.

LIFETIME EMPLOYMENT, LABOUR MOBILITY AND ENTERPRISE UNIONS

Kato (2000) describes the practice of lifetime employment as an indispensible ingredient of successful Japanese management. The lifetime employment system is related to the fact that Japanese companies avoid dismissals in order to protect their investment in training employees (Flath, 2005). Under this practice, an employee is hired by a company immediately after school graduation, receives training on the job, and remains with the same company until his retirement (Raisan and Hashimoto, 1985) or the employee changes fewer companies over his lifetime (Flath, 2005). A long-term employment relationship is a principal reason for Japan's high labour productivity (Raisan and Hashimoto, 1985).

The lifetime employment resulted in lower labour mobility in Japan. Surveys demonstrate that this system has not changed over the years. Kato (2000) in his survey presented quantitative evidence on changes in the prevalence of lifetime employment from the 1980s to the 1990s. He found little evidence of decline in lifetime employment and confirmed that the practice of lifetime employment applies only to men and that long-term employment is more prevalent in Japan than in the USA, as shown in the Figure 5. Between the 1980s and 1990s 55.22% of Japanese male employees, aged 20-24 with more than 5 years of tenure, retained the same job 15 years later but only 28.45% did so in the USA. Each age group shows similar results, whereby Japan has considerably higher retention rates than the USA.

1982 (1983)

|

Japan (1982 – 97)

|

U.S. (1983 – 98)

|

|

Age

|

Tenure (years)

|

15 – year retention rate (%)

|

15 – year retention rate (%)

|

15 – 19

|

0 – 4

|

39.99

|

4.59

|

20 – 24

|

0 – 4

5 +

|

51.08

55.22

|

13.92

28.45

|

25 – 34

|

0 – 4

5 +

|

52.24

73.64

|

20.13

48.14

|

35 – 39 (35 – 44)

|

0 – 4

5 +

|

46.65

78.44

|

22.06

52.14

|

Figure 5: Fifteen-year job retention rates of male employees in Japan and the United States

Source: Kato 2000

In 2011 Japan’s Statistic Bureau and Kosugi carried out a similar survey on labour’s mobility in Japan, both showing the low labour mobility in this decade. Labour dualism is a characteristic of Japanese labour market which is divided into regular or permanent workers and non-regular or temporary workers (OECD, 2011).

Figure 6 shows there were 51.11 million employees of whom 65.7 per cent were regular staff members in 2010. The ratio of regular staff members among all male employees was 81.1%, while the corresponding ratio for females was 46.2%, which is consistent with Kato’s (2000) survey. Women are mostly temporary workers while men are regular staff members.

(in 000)

|

||||

Employees*

|

Regular staff

|

Percentage

|

Non– regular staff

|

|

Total

|

51,110

|

33,550

|

65.7

|

17,550

|

Males

|

28,480

|

23,090

|

81.1

|

5,390

|

Females

|

22,630

|

10,460

|

46.2

|

12,180

|

*Excluding company executives.

|

||||

Figure 6: Employment by employment pattern (2010)

Source: Statistical Handbook of Japan 2011 by Statistics Bureau

Kosugi’s recent study showed that only 13.9% employees changed their status, from non-regular to regular. Regular workers represent 75% of men and only 34.9 % of women, hence women are mostly hired as temporary workers and they rarely make the transition to permanent status, which demonstrates the strong position of men in Japan. Since the transition rate from non-regular to regular status is low, a worker who accepts non-regular employment faces a high probability of never escaping this category, with its accompanying low wages, reduced training, precarious jobs and limited social insurance coverage (OECD, 2011).

Survey of 4000 workers between the ages 25 and 44 (Kosugi,2010), in %

|

Men

|

Women

|

Total

|

Regular workers

|

75.0

|

34.9

|

58.4

|

Workers

hired directly from school who maintain regular status

|

30.9

|

13.5

|

23.7

|

Workers

who changed jobs while maintaining regular status

|

17.7

|

3.7

|

11.9

|

Non

– regular workers who became regular workers in a different firm

|

11.5

|

9.6

|

10.7

|

Non

– regular workers who became regular workers in the same firm

|

3.6

|

2.5

|

3.2

|

Workers

who were self-employed or voluntarily unemployed

|

11.3

|

5.7

|

9.0

|

Non regular workers

|

8.6

|

53.8

|

27.3

|

Workers

with experience as regular workers

|

1.3

|

7.4

|

3.8

|

Workers

who have remained non-regular workers

|

3.9

|

31.1

|

15.2

|

Self-employed executives and family

workers

|

16.4

|

11.4

|

14.3

|

Workers

with experience changing from non-regular to regular status

|

1.7

|

1.1

|

1.5

|

Figure 7: Employees by past employment history

Source: OECD 2011

Japan, as many other countries, also has labour unions but most Japanese unions are enterprise unions which collect the employees of a single firm, not the whole industry (Flath, 2005). In Japan, enterprise unions account for more than 90 per cent of all unions and organized workers (Jeong, Aguliera, 2008). The prevalent members of enterprise unions are regular workers of large manufacturing company. Therefore, union members are workers employed in the system of the lifetime employment and seniority-based wages (Flath, 2005), which means that non-regular workers, mostly women are in disadvantageous situation. The enterprise unions utilize negotiations and labour-management consultations to improve working conditions, to monitor corporate activities, and to provide services to their members .

Jeong and Aguliera (2008) see the enterprise unionism in Japan as a result of labour’s failure in institutionalizing horizontal unions where state and management played a huge role in defeating the horizontal and industrial unionism which were seen as the threats to the government and large companies.

CONCLUSION

Traditional Japanese labour market practices, such as the lifetime employment, seniority-based wage system and labour dualism are no longer appropriate since Japan’s economic growth is low, the population is ageing, unemployment rising and globalisation shifted the balance of power which has dented Japan’s long term competitive advantage. Due to globalisation many companies in developed countries have transferred their production and manufacturing plants to developing and emerging markets since production is cheaper there and in that way they can cope in increasingly competitive markets. Japan is expected to do the same. Because of that the ratio of primary and secondary industry will reduce and Japan will need to re-educate part of its workers so they are able to work in the service sector. All this can lead to the changes of the lifetime employment and payment systems in Japan. Labour market dualism must be revised for the same reason and economic policy and management attitudes must adapt in order for Japan to cope in an increasingly competitive environment. Low labour mobility, lifetime employment and nenko system mean lower competition between workers and these practices can reduce the incentive to work hard for the company. Since the population of Japan is rapidly aging, they should draw more women into the labour force, but in order to do that, sex discrimination must be addressed. Women should be able to work and raise a family at the same and this can foster population growth. Furthermore, Japan should invest more in the education of women and they need to be paid at the same rate as men so women can become career-minded workers.

References

1. Blomstrom, M., Ganges, B., & Croix, S., (2001) Japan’s New Economy: Continuity and change in the twenty - first century. New York: Oxford University Press.

2. Flath, D., (2005) The Japanese economy, 2nd Edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

3. Hashimoto, M., Raisan, J. (1985) Employment Tenure and Earnings Profiles in Japan and the United States. The American Economic Review, 75 (4) pp. 721-735

4. Jeong, D.Y., Aguliera, R.V. (2008). The Evolution of Enterprise Unionism in Japan: A Socio-Political Perspective. British Journal of Industrial Relations 46 (1), pp. 98-132

5. Kato, T., (2000) The end of lifetime employment in Japan? Evidence from National Surveys and Field Research, Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 15, pp. 489-514.

6. Naughton, B. (2007) the Chinese Economy: Transitions and Growth. Cambridge: MIT

7. OECD Economic Surveys: Japan [online]. Available at: http://www.keepeek.com/Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/economics/oecd-economic-surveys-japan-2011/labour-market-reforms-to-improve-growth-and-equity_eco_surveys-jpn-2011-8-en

8. The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training [online]. Available at: http://www.jil.go.jp/english/estatis/databook/2011/02.html

The Statistics Bureau and the Director-General for Policy Planning of Japan [online]. Available at: www.stat.go.jp

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.